Topological Photonics for Robust Light Manipulation

Topological photonics leverages concepts from topological physics, originally developed in condensed matter systems, to control the flow of light in unprecedented ways. By designing photonic structures with non-trivial topological properties, it's possible to create light states that are inherently robust against defects, disorder, and sharp bends. This robustness stems from the topological protection of specific states, most notably edge states, which are guaranteed to exist at the interface between topologically distinct domains due to the bulk-boundary correspondence. This principle has opened exciting avenues for creating highly efficient and fault-tolerant photonic devices for applications ranging from optical communication and computing to sensing and lasing.

This article explores the foundations and frontiers of topological photonics for robust light manipulation. We will delve into the core mechanisms enabling topological protection, examine the unique possibilities offered by extending these concepts into non-Hermitian (systems with gain or loss) and higher-order topological regimes, and discuss the emerging challenges and opportunities in this rapidly evolving field. The focus is not merely on reporting existing findings but on synthesizing insights across different sub-domains and speculating on future directions where topological principles might lead to novel optical functionalities.

Foundations: Topological Protection and Edge States

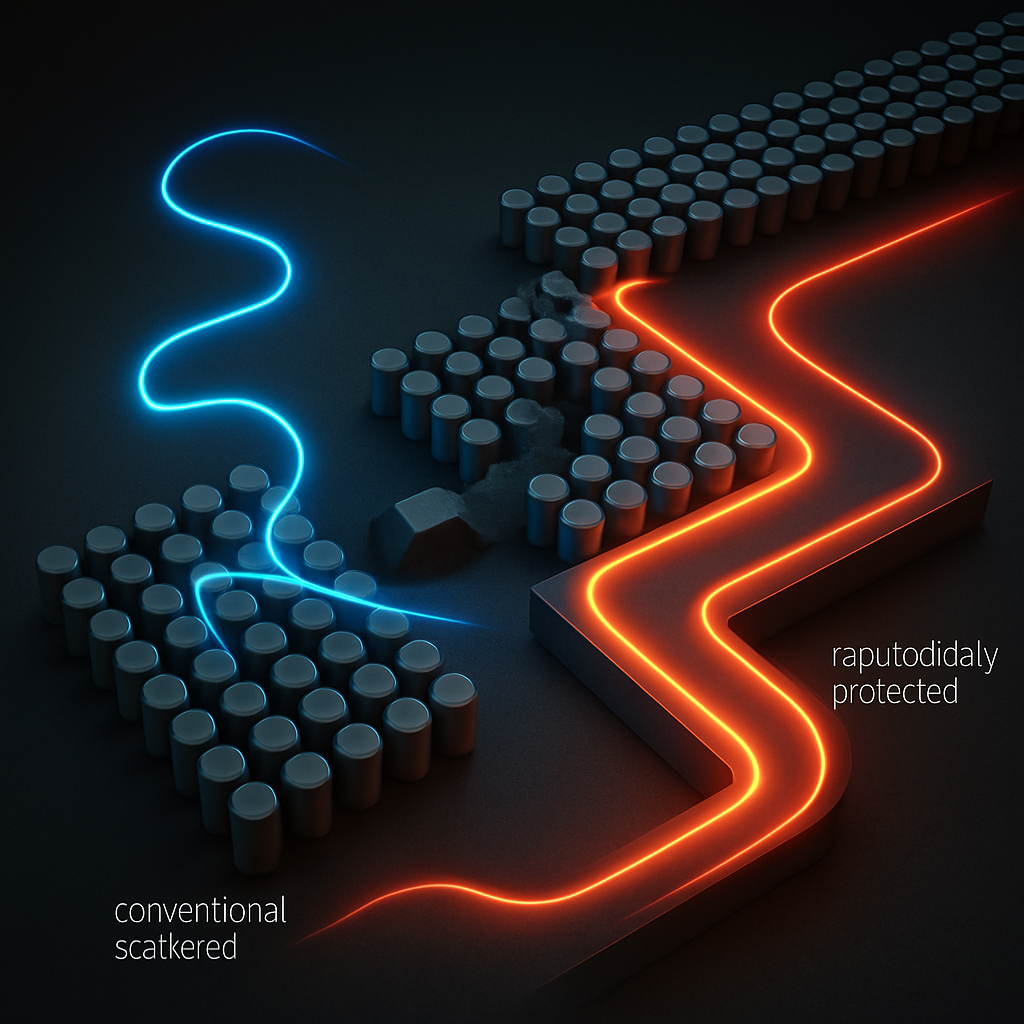

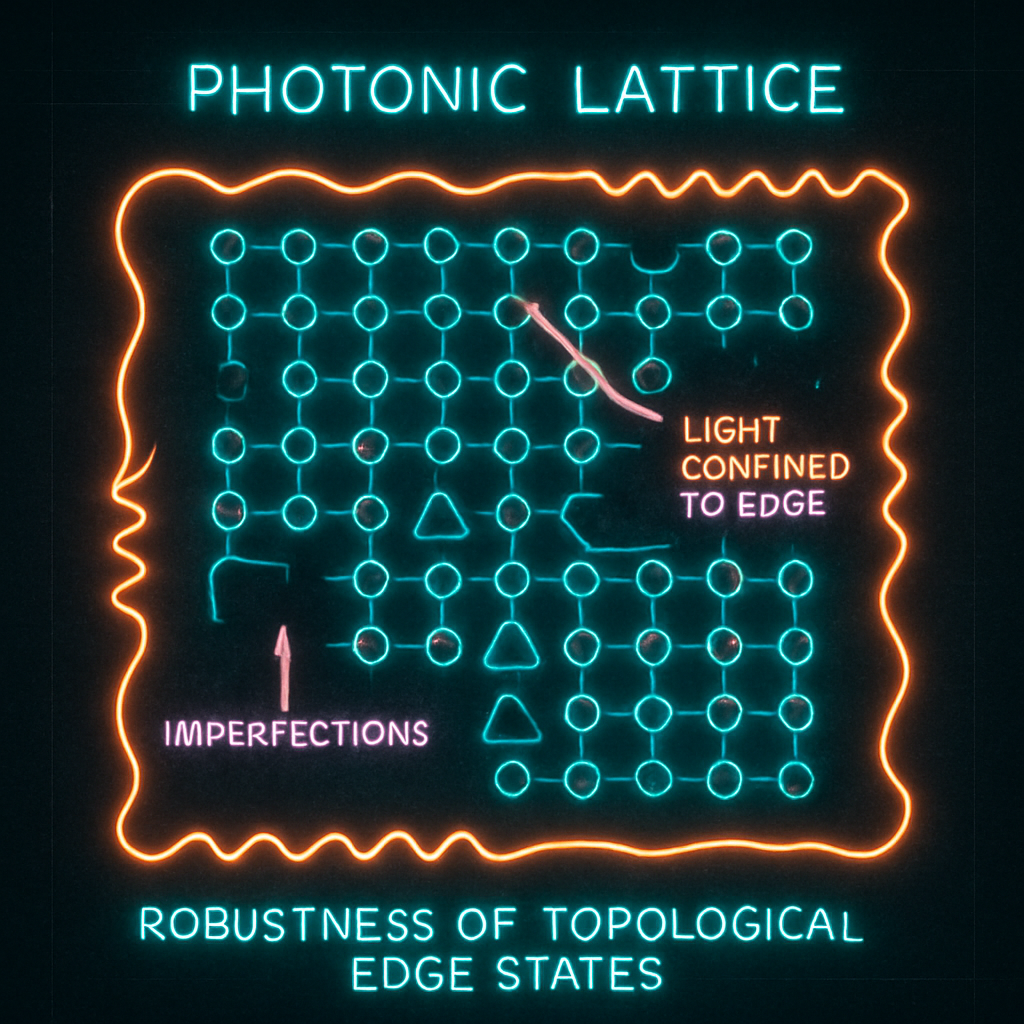

The cornerstone of topological photonics is the existence of topologically protected edge states. These states arise in engineered photonic materials, such as photonic crystals or coupled waveguide/resonator arrays, whose band structure possesses a non-trivial topological invariant (e.g., the Chern number). Analogs of the quantum Hall effect (requiring broken time-reversal symmetry, often achieved via magneto-optic materials or synthetic gauge fields) and the quantum spin Hall effect (utilizing effective spin degrees of freedom for photons, like polarization or pseudospin related to lattice symmetries) have been realized. Valley Hall effect topological insulators, utilizing broken inversion symmetry in specific lattice structures (like honeycomb lattices), provide another pathway using geometric phase concepts without needing magnetic fields, enabling broadband and fabrication-tolerant devices like topological 3-dB couplers (Tang et al., 2024).

The defining characteristic of these edge states is their immunity to backscattering from local defects or structural imperfections that preserve the underlying topology. Light propagating in these edge channels can navigate sharp corners and bypass obstacles with minimal loss, a feature highly desirable for integrated photonic circuits where fabrication imperfections are inevitable (Yan et al., 2024). Various platforms, including silicon photonics (Xu et al., 2016), femtosecond laser-written waveguides (Yan et al., 2024), plasmonic nanochains (Yan et al., 2025), and microwave metamaterials (Jouanny et al., 2025), have successfully demonstrated topologically protected light transport. The robustness arises because the edge states exist within the bulk bandgap, and smoothly deforming the structure or adding local defects typically cannot close this gap and eliminate the topological distinction that mandates the edge state's existence. Even exotic variations like Jackiw-Rebbi states at domain walls engineered via Dirac-mass distributions in metasurfaces offer topologically rooted beam control (Choi et al., 2025).

Expanding the Toolkit: Non-Hermitian Topological Photonics

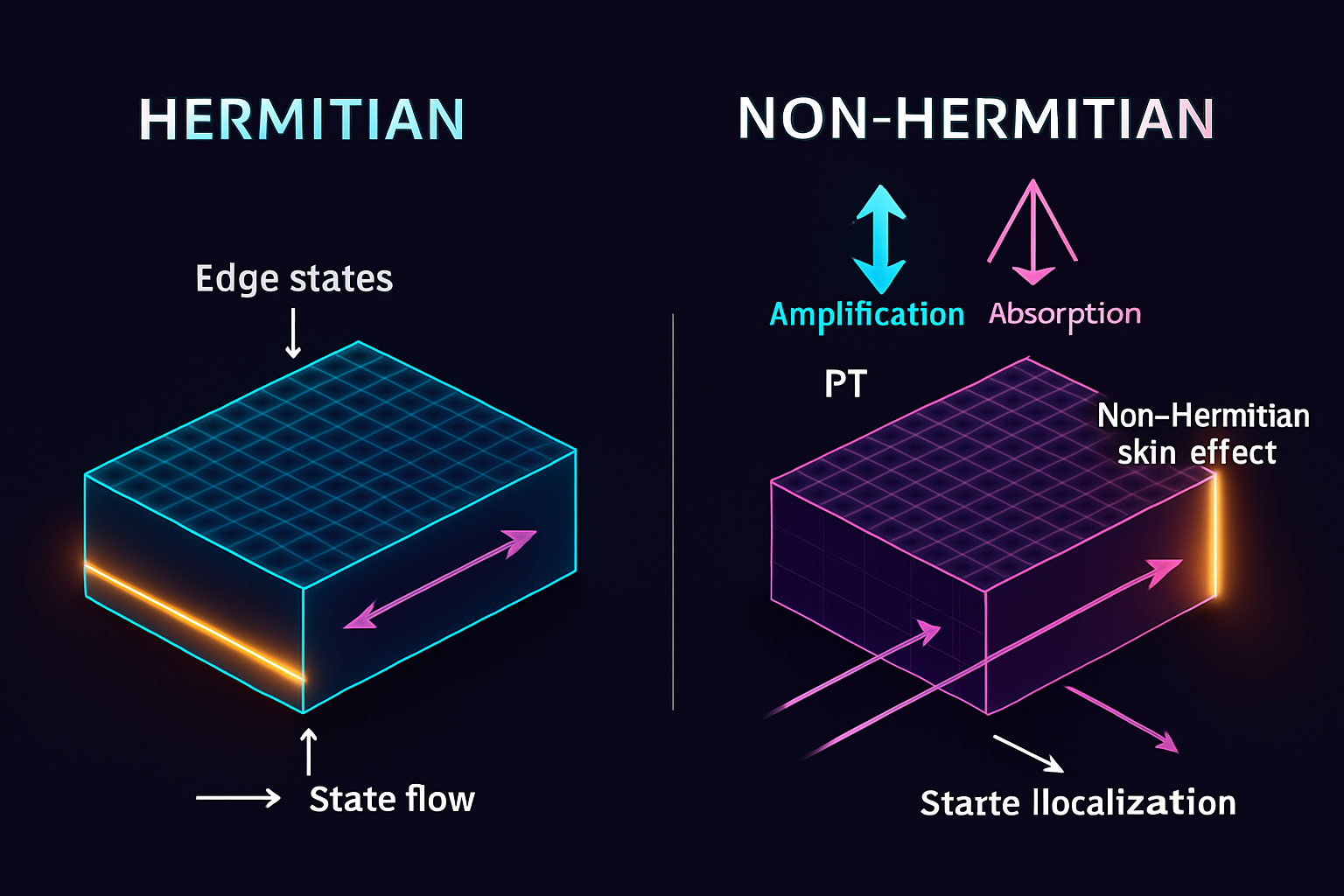

Introducing non-Hermiticity—gain and loss—into photonic systems dramatically expands the landscape of topological phenomena, bridging topological matter concepts with gain/loss engineering (Ye et al., 2024). While traditional topological protection relies on Hermitian Hamiltonians, non-Hermitian systems exhibit unique features like the non-Hermitian skin effect (NHSE) and exceptional points (EPs). The NHSE describes the anomalous localization of a macroscopic number of bulk eigenstates at the system boundaries, a phenomenon highly sensitive to boundary conditions (Ammari et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2024) and observable even transiently in passive systems (Gu et al., 2022) or incoherent quantum walks (Longhi, 2024). This boundary localization itself can lead to directional transport phenomena, fundamentally distinct from Hermitian topological protection, and has been explored in laser arrays (Liu et al., 2022) and mathematically characterized (Ammari et al., 2024).

Parity-time (PT) symmetry, a specific class of non-Hermiticity, initially promised real spectra but its breaking leads to complex eigenvalues and unique dynamics. Interfaces between different PT phases (symmetric vs. broken) can host robust interface states, potentially linking robustness to quantum phase transitions rather than solely topology (Zhao et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2018). Non-Hermitian systems can realize topological phases with no Hermitian counterpart, such as unidirectional transport immune to defects induced by non-Hermitian coupling or imaginary gauge fields (Du et al., 2020; Longhi et al., 2015). Recent works explore dynamically controlled NHSE in synthetic dimensions (Zheng et al., 2024), using PT-symmetry breaking to activate skin modes selectively (Lei et al., 2024), and probing NHSE signatures via steady-state dynamics (Ye et al., 2024). The interplay is complex: can the directionality of NHSE be robustified or controllably toggled, or does its inherent boundary sensitivity fundamentally limit topological robustness in these systems? Exploring this tension, potentially via dualities linking non-Hermiticity to curved space (Lv et al., 2022), or understanding universal behaviors near non-Hermitian phase transitions (Wei & Jin, 2017), remains a key research direction.

Beyond Edges: Higher-Order and Exotic Topological Phases

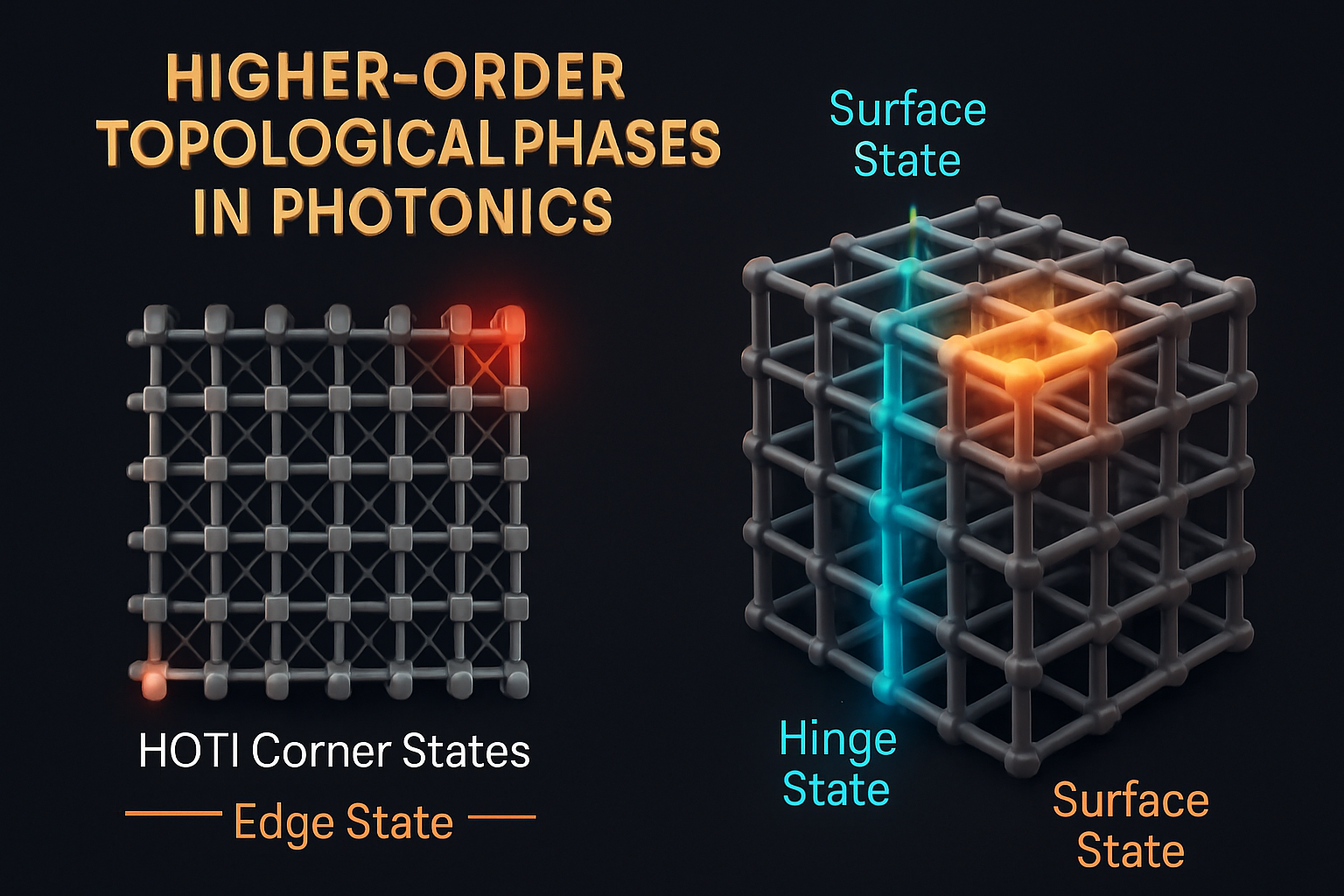

The concept of topology in photonics has extended beyond edge states (1D boundaries of 2D systems) to higher-order topological insulators (HOTIs). These systems possess topological states localized at boundaries of lower dimensions: hinge states (1D boundaries of 3D systems) or corner states (0D boundaries of 2D or 3D systems). This allows for topological protection in geometries previously inaccessible, potentially enabling novel resonator designs or light confinement strategies. Realizing 3D photonic HOTIs has been challenging due to the vectorial nature of light and radiative losses, but recent breakthroughs using metal-cage photonic crystals have demonstrated coexisting surface, hinge, and corner states robust and self-guided even within the light cone (Wang et al., 2025). Valley photonic crystals with engineered structures like dendritic units also show promise for realizing ultrabroadband valley transmission and switchable corner states (Li et al., 2024).

Beyond HOTIs, other exotic topological phases are being explored. Photonic axion insulators, analogous to their electronic counterparts, are predicted to host chiral hinge states and exhibit unique magnetoelectric effects, bridging topology and magnetism in photonics (Lai et al., 2025; Devescovi et al., 2024). Experimental demonstrations are emerging, showcasing non-coplanar chiral hinge transport in 3D structures. Concepts like topological pumps, where states are robustly transported by cyclically varying system parameters (Fedorova et al., 2020), are being extended to higher-order regimes protected by boundary topology (Wang et al., 2024), enabling corner-edge-corner transport. The exploration of topology in hyperbolic lattices (Chen et al., 2025; Hu et al., 2024), the role of long-range interactions (Kim et al., 2024), topological states in time and space-time (Feis et al., 2025), and connections to phenomena like Landau levels in laser systems (Pan et al., 2025) further push the boundaries, suggesting a rich and expanding landscape for topological light control.

Conclusion

Topological photonics has rapidly transitioned from theoretical curiosity to a vibrant experimental field, offering powerful strategies for robust light manipulation. The initial focus on edge states protected by bulk topology has expanded significantly, incorporating the rich physics of non-Hermitian systems and the geometric possibilities of higher-order and exotic topological phases. Non-Hermiticity introduces phenomena like the skin effect and allows access to novel topological invariants and control mechanisms (e.g., PT-symmetry breaking), while HOTIs provide pathways for light localization at corners and hinges, moving beyond simple waveguide geometries.

Looking ahead, several frontiers promise exciting developments. The deep interplay between topology, non-Hermiticity, nonlinearity, quantum effects (Gao et al., 2024; Wan et al., 2025), and even material structure (An et al., 2024; Park et al., 2024) is ripe for exploration. Can the sensitivity and directionality of NHSE be combined with topological features for dynamically reconfigurable, robust pathways (Zheng et al., 2024; Lei et al., 2024)? Can topological protection stabilize nonlinear or active systems like lasers (Liu et al., 2022; Dikopoltsev et al., 2025)? Addressing practical challenges like mitigating out-of-plane losses (Wong et al., 2024) and achieving robust topological effects with broadband operation (Tang et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024) and fabrication tolerance remains crucial. Exploring new platforms, including synthetic dimensions (Dikopoltsev et al., 2025; Yan et al., 2025), hyperbolic metamaterials (Hu et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2025), and connections to other wave systems like acoustics (Zhao et al., 2025; Li et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024), will continue to spur innovation. The synthesis of topological concepts with advanced photonic design, potentially aided by AI (Ao et al., 2025), promises transformative advances in manipulating light for science and technology.

References

- Ammari, H., Barandun, S., Cao, J., Davies, B., & Hiltunen, E. O. (2024). Mathematical Foundations of the Non-Hermitian Skin Effect. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00205-024-01976-y

- An, T. et al. (2024). Strain to shine: stretching-induced three-dimensional symmetries in nanoparticle-assembled photonic crystals. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49535-z

- Ao, Y., Li, S., & Duan, H. (2025). Artificial Intelligence-Aided Design (AIAD) for Structures and Engineering: A State-of-the-Art Review and Future Perspectives. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-025-10264-1

- Chen, J., Yang, L., & Gao, Z. (2025). Dynamic transfer of chiral edge states in topological type-II hyperbolic lattices. Communications Physics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01990-w

- Chen, L., Niu, Z.-X., & Xu, X. (2024). Dynamic protected states in the non-Hermitian system. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72557-y

- Choi, Y. S. et al. (2025). Topological beaming of light: proof-of-concept experiment. Light: Science & Applications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-01799-w

- Dash, D., Saini, J., & Goyal, A. K. (2025). Performance analysis of hyperbolic graded topological resonator for biosensing applications. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94062-6

- Derevyanko, S. (2019). Disorder-aided pulse stabilization in dissipative synthetic photonic lattices. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49259-x

- Devescovi, C. et al. (2024). Axion topology in photonic crystal domain walls. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50766-3

- Dikopoltsev, A. et al. (2025). Collective quench dynamics of active photonic lattices in synthetic dimensions. Nature Physics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-025-02880-2

- Du, L., Zhang, Y., & Wu, J.-H. (2020). Controllable unidirectional transport and light trapping using a one-dimensional lattice with non-Hermitian coupling. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58018-2

- Fedorova, Z., Qiu, H., Linden, S., & Kroha, J. (2020). Observation of topological transport quantization by dissipation in fast Thouless pumps. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17510-z

- Feis, J. et al. (2025). Space-time-topological events in photonic quantum walks. Nature Photonics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-025-01653-w

- Gao, J. et al. (2024). Quantum topological photonics with special focus on waveguide systems. npj Nanophotonics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-024-00034-5

- Gu, Z. et al. (2022). Transient non-Hermitian skin effect. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35448-2

- Hu, S. et al. (2024). Hyperbolic metamaterial empowered controllable photonic Weyl nodal line semimetals. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47125-7

- Jouanny, V. et al. (2025). High kinetic inductance cavity arrays for compact band engineering and topology-based disorder meters. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58595-8

- Kim, G., Suh, J., Lee, D., Park, N., & Yu, S. (2024). Long-range-interacting topological photonic lattices breaking channel-bandwidth limit. Light: Science & Applications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-024-01557-4

- Lai, H.-S. et al. (2025). Photonic axion insulator with non-coplanar chiral hinge transport. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59214-2

- Lei, Z., Lee, C. H., & Li, L. (2024). Activating non-Hermitian skin modes by parity-time symmetry breaking. Communications Physics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01591-z

- Li, K. et al. (2025). Observation of chiral Landau levels in a synthetic acoustic Weyl semimetal. Communications Physics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02053-w

- Li, M. et al. (2024). Ultrabroadband valley transmission and corner states in valley photonic crystals with dendritic structure. Communications Physics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01712-8

- Liu, Y. G. N. et al. (2022). Complex skin modes in non-Hermitian coupled laser arrays. Light: Science & Applications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-022-01030-0

- Longhi, S. (2024). Incoherent non-Hermitian skin effect in photonic quantum walks. Light: Science & Applications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-024-01438-w

- Longhi, S., Gatti, D., & Valle, G. D. (2015). Robust light transport in non-Hermitian photonic lattices. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13376

- Lv, C., Zhang, R., Zhai, Z., & Zhou, Q. (2022). Curving the space by non-Hermiticity. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29774-8

- Pan, J. et al. (2025). Photonic Landau levels in an astigmatic frequency-degenerate laser. Communications Physics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02013-4

- Pan, M., Zhao, H., Miao, P., Longhi, S., & Feng, L. (2018). Photonic zero mode in a non-Hermitian photonic lattice. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03822-8

- Park, H., Oh, S. S., & Lee, S. (2024). Surface potential-adjusted surface states in 3D topological photonic crystals. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56894-6

- Tang, G.-J. et al. (2024). Broadband and fabrication-tolerant 3-dB couplers with topological valley edge modes. Light: Science & Applications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-024-01512-3

- Wan, T., & Yang, Z. (2025). Non-Hermitian interacting quantum walks of correlated photons. Communications Physics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02038-9

- Wang, Z. et al. (2025). Realization of a three-dimensional photonic higher-order topological insulator. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58051-7

- Wang, Z. et al. (2024). Higher-order topological transport protected by boundary Chern number in phononic crystals. Communications Physics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01681-y

- Wei, B.-B., & Jin, L. (2017). Universal Critical Behaviours in Non-Hermitian Phase Transitions. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07344-z

- Wong, S., Loring, T. A., & Cerjan, A. (2024). Classifying topology in photonic crystal slabs with radiative environments. npj Nanophotonics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-024-00021-w

- Xu, Y.-L. et al. (2016). Experimental realization of Bloch oscillations in a parity-time synthetic silicon photonic lattice. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11319

- Yan, W., Zhang, B., & Chen, F. (2024). Photonic topological insulators in femtosecond laser direct-written waveguides. npj Nanophotonics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-024-00040-7

- Yan, Q. et al. (2025). Near-field imaging of synthetic dimensional integrated plasmonic topological Harper nanochains. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57747-0

- Ye, R. et al. (2024). Observing non-Hermiticity induced chirality breaking in a synthetic Hall ladder. Light: Science & Applications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-024-01700-1

- Zhao, H., Longhi, S., & Feng, L. (2015). Robust Light State by Quantum Phase Transition in Non-Hermitian Optical Materials. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17022

- Zhao, S. et al. (2025). Topological acoustofluidics. Nature Materials. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02169-y

- Zheng, X. et al. (2024). Dynamic control of 2D non-Hermitian photonic corner skin modes in synthetic dimensions. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55236-4