Mycorrhizal Neural Networks: Engineering Fungal-Plant Symbiosis for Decentralized Environmental Remediation

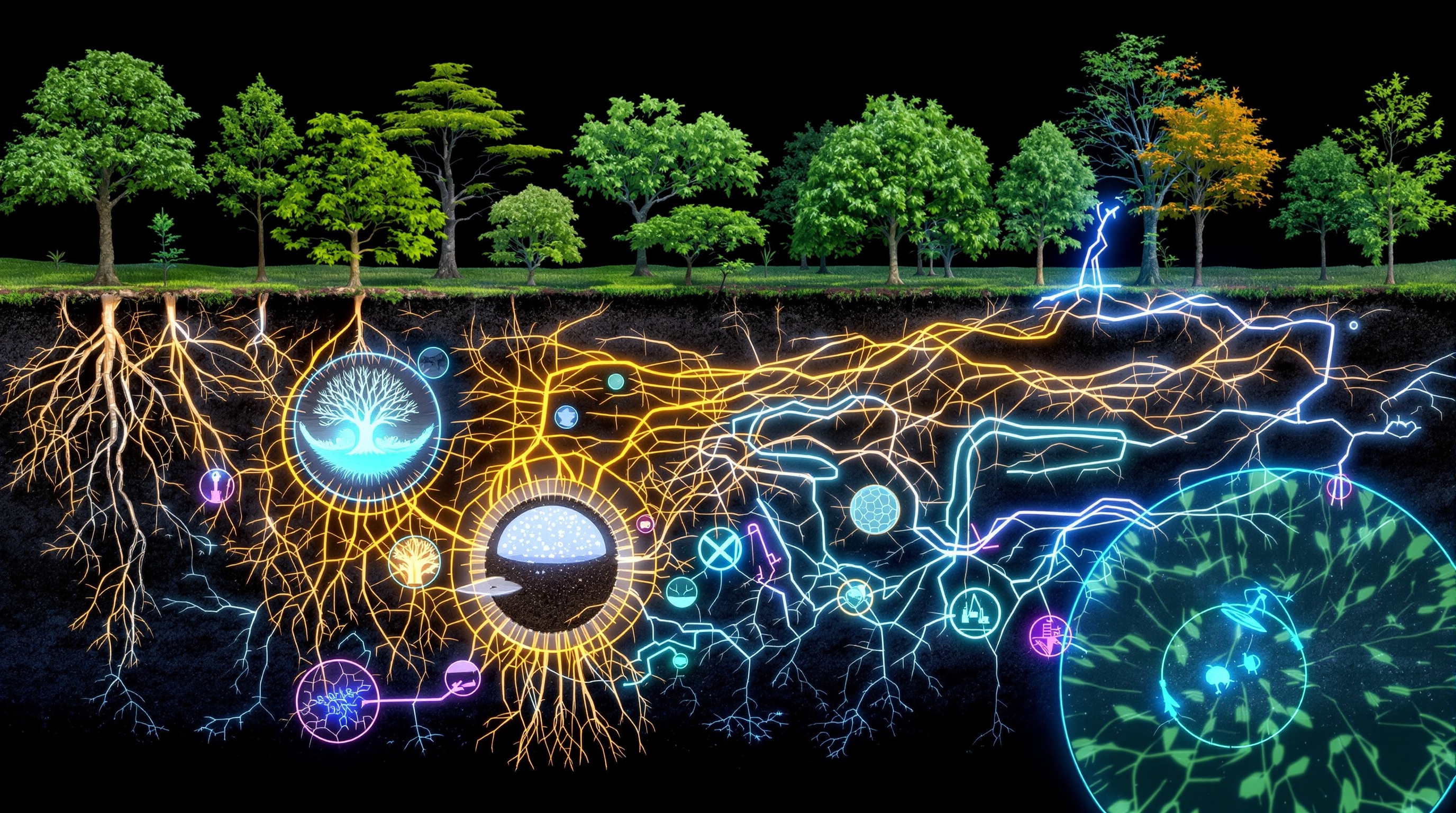

The accelerating convergence of climate disruption, soil degradation, and environmental contamination presents an urgent imperative for radically reimagining ecosystem restoration strategies. Traditional remediation approaches—relying on centralized, energy-intensive technologies—often fail to address the spatial heterogeneity and ecological complexity inherent in contaminated landscapes. Yet beneath our feet exists a sophisticated biological infrastructure that has evolved over 400 million years: the mycorrhizal symbiosis between fungi and plant roots. Recent evidence suggests these networks possess emergent properties reminiscent of distributed computing systems—exchanging nutrients, carbon, and potentially even information across vast spatial scales through hyphal networks connecting multiple plants (Nuland et al., 2025; Parise et al., 2025).

This review proposes a provocative synthesis: that mycorrhizal networks can be conceptualized as "environmental neural networks" capable of decentralized sensing, resource allocation, and adaptive remediation responses. Drawing on cutting-edge research spanning mycorrhizal ecology, phytoremediation, synthetic biology, and network theory, we explore how engineering fungal-plant symbioses could enable distributed, autonomous systems for detecting and remediating soil contaminants. Specifically, we examine: (1) the networked architecture and functional capacity of common mycorrhizal networks (CMNs), (2) mechanisms by which mycorrhizae facilitate contaminant immobilization and plant tolerance, (3) emerging biotechnological approaches for engineering enhanced remediation capabilities, and (4) the design principles for implementing mycorrhizal-based remediation as a scalable, decentralized technology. Critically, we argue that the true innovation lies not merely in optimizing single fungal strains, but in harnessing the emergent, system-level properties of interconnected mycorrhizal communities operating across contaminated landscapes.

The Architecture of Mycorrhizal Neural Networks: Structure and Function

Mycorrhizal fungi establish symbioses with approximately 90% of terrestrial plant species, forming two dominant functional types: arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi (Glomeromycotina) and ectomycorrhizal (EM) fungi (primarily Basidiomycota and Ascomycota). While both facilitate nutrient exchange, recent research reveals profound differences in their network topology and functional specialization. AM fungi penetrate root cortical cells to form arbuscules—intricate branching structures for bidirectional nutrient transfer—while extending extensive extraradical hyphal networks through the soil matrix. EM fungi form a hyphal sheath around fine roots and a Hartig net penetrating between epidermal and cortical cells, creating a fundamentally different architectural interface (Jiang et al., 2025; Pena & Tibbett, 2024).

The concept of "common mycorrhizal networks" describes the physical interconnection of multiple plants through shared fungal mycelia—a phenomenon now documented across diverse ecosystems from temperate forests to agricultural systems (Snyder et al., 2025; Wei et al., 2025). These networks exhibit scale-free properties similar to neural architectures, with certain fungal "hubs" connecting disproportionately more plants than others. Keystone fungal taxa—including Glomus and Septoglomus in AM systems—play critical structural roles in network stability, with their removal triggering cascading effects on network connectivity and function (Fernández-González et al., 2025; Marrassini et al., 2025). Remarkably, fungal succession studies reveal temporal dynamics in network composition, with early colonizers establishing initial pathways that late-stage fungi modify and optimize (Ryadin et al., 2025).

Perhaps most intriguing is emerging evidence that mycorrhizal networks possess rudimentary information processing capabilities. Electrical potential measurements in fungal mycelia reveal week-long oscillation cycles and directional signal propagation from resource-rich patches (such as wood baits) to peripheral regions (Fukasawa et al., 2024). While the functional significance remains debated, such electrical dynamics suggest mechanisms for coordinating resource acquisition across the network. Furthermore, mycorrhizal colonization patterns respond to plant stress signals, including strigolactone and flavonoid exudates, enabling plants to actively recruit symbiotic partners during nutrient limitation or pathogen attack (Soliman et al., 2025; Moreno et al., 2025). This bidirectional signaling creates a feedback loop where plant physiological state modulates fungal behavior, which in turn reshapes plant metabolism—a hallmark of adaptive systems.

Mycorrhizal-Mediated Mechanisms of Environmental Remediation

The remediation potential of mycorrhizal symbioses emerges from multiple synergistic mechanisms operating at molecular, cellular, and ecosystem scales. First, mycorrhizal fungi dramatically expand the effective root exploration volume—AM fungal hyphae can extend 10-100 times the root surface area, while EM mycelial cords penetrate organic horizons inaccessible to plant roots alone (Coleman et al., 2025). This spatial expansion enables access to spatially heterogeneous contaminant pools, transforming plants into biological sensors capable of detecting and responding to pollutants across the rhizosphere.

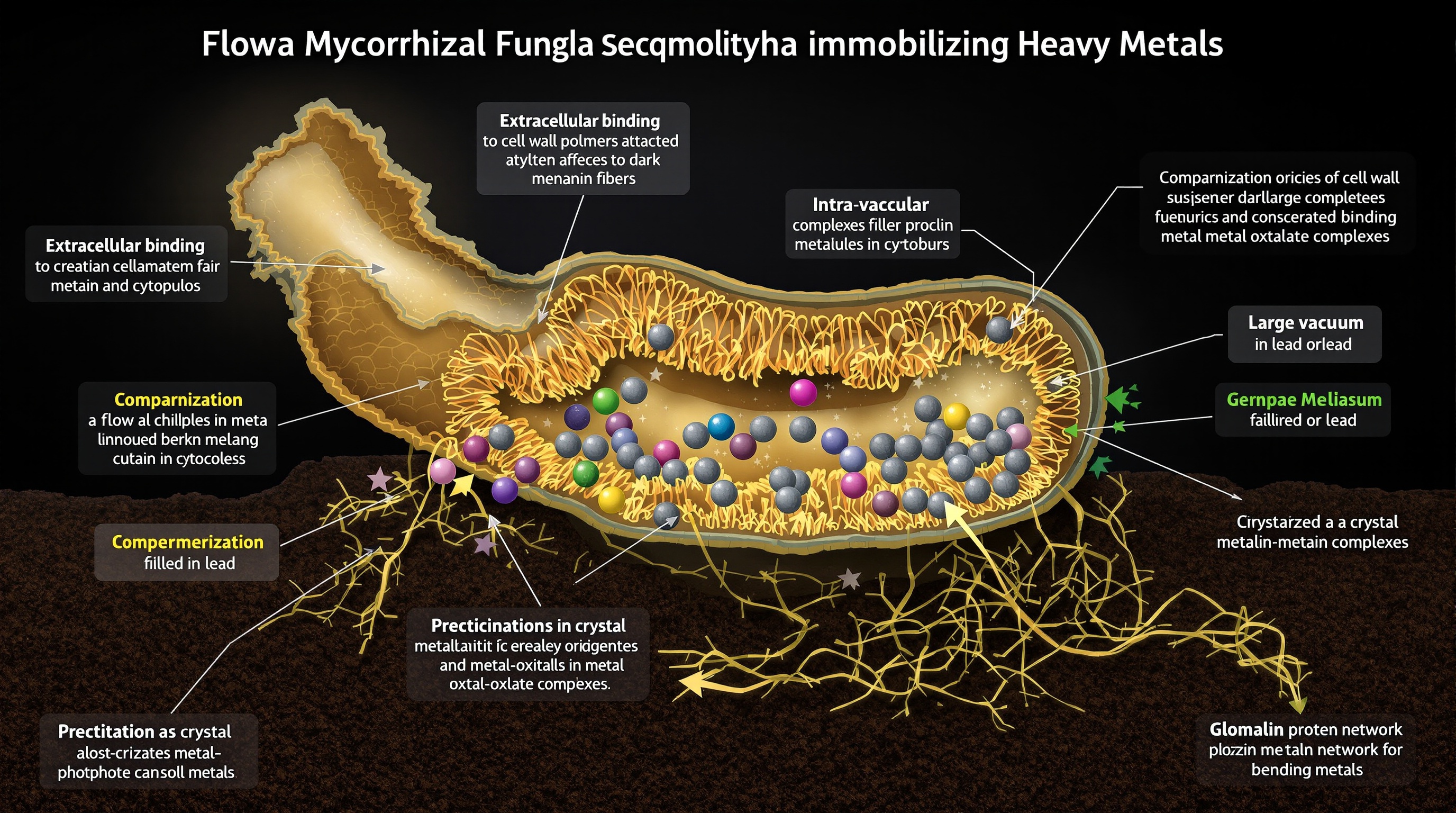

Heavy metal immobilization represents one of the most well-characterized remediation pathways. Mycorrhizal fungi sequester toxic metals through multiple mechanisms: (1) extracellular binding to fungal cell wall chitin and melanin pigments, (2) intracellular chelation by metallothioneins and phytochelatins, (3) compartmentalization in fungal vacuoles, and (4) precipitation as insoluble phosphate, oxalate, or carbonate complexes (Tang et al., 2025; Usama et al., 2025). Critically, glomalin-related soil proteins (GRSP)—glycoproteins secreted by AM fungi—bind heavy metals in soil aggregates, reducing bioavailability and preventing metal translocation to plant shoots. Studies demonstrate that combined application of AM fungi and glomalin reduces cadmium concentrations in plant grains by up to 89% while simultaneously improving soil enzyme activity and structure (Usama et al., 2025).

The functional specialization of different mycorrhizal types suggests opportunities for tailored remediation strategies. Recent comparative studies show that EM fungi excel at accessing organic nitrogen and phosphorus through secretion of hydrolytic enzymes, while AM fungi enhance plant uptake of mineral nutrients, particularly under low phosphorus availability (Pena & Tibbett, 2024; Severo et al., 2025). This functional complementarity could be exploited in mixed plant communities where both mycorrhizal types coexist, creating multi-tiered remediation systems addressing both organic and inorganic contaminant fractions.

Emerging research reveals that mycorrhizal inoculation fundamentally reprograms plant metabolism and stress responses. Transcriptomic analyses of mycorrhizal plants show upregulation of defense genes, antioxidant enzymes, and stress-responsive metabolites (Wen et al., 2025; Yang et al., 2025). Under drought stress, mycorrhizal colonization increases soluble sugar concentrations, modulates hormone levels (reducing cytokinins while enhancing peroxidase activity), and improves water use efficiency—adaptations that could enable phytoremediation in water-limited contaminated sites (Yang et al., 2025). Remarkably, the benefits extend beyond individual plants: mycorrhizal networks redistribute resources from unstressed to stressed plants, potentially enabling collective stress resilience across connected plant communities.

Engineering Enhanced Remediation: Synthetic Biology Approaches

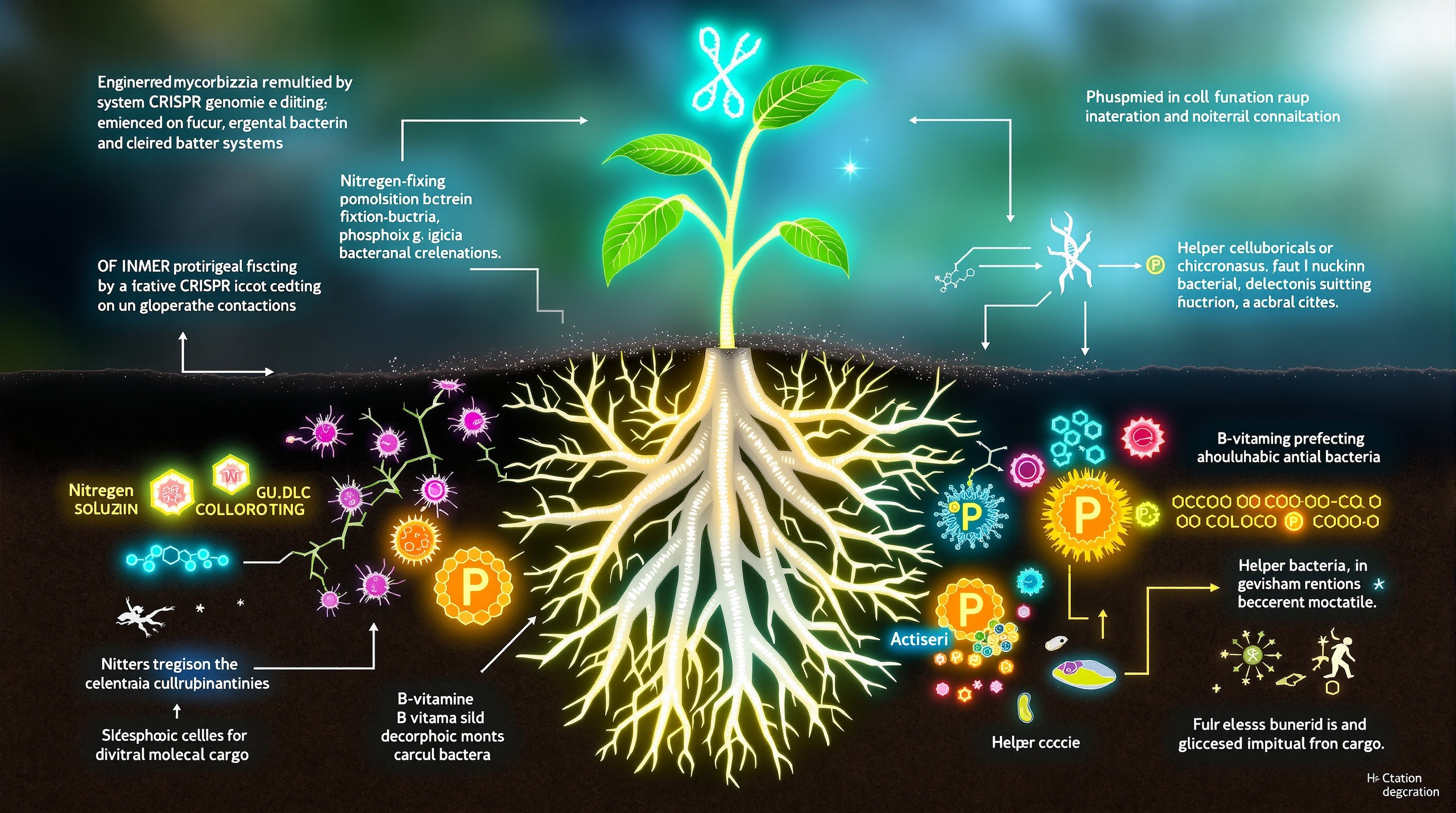

While natural mycorrhizal symbioses offer substantial remediation benefits, emerging biotechnological approaches promise to engineer enhanced capabilities that transcend evolutionary constraints. One frontier involves identifying and manipulating the genetic determinants of metal tolerance and accumulation. Comparative genomic analyses of hyperaccumulator plants and metal-resistant fungal strains have revealed candidate genes encoding metal transporters, chelators, and stress response regulators (Lax et al., 2025). CRISPR-based genome editing could potentially transfer these genetic modules into agronomically important crop species or mycorrhizal fungi, creating designer symbioses optimized for specific contaminant profiles.

Synthetic microbial consortia (SynComs) represent another powerful approach for augmenting mycorrhizal remediation capacity. Rather than relying on single fungal inoculants, SynComs combine functionally complementary strains—nitrogen-fixing bacteria, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria, and mycorrhizal fungi—selected for non-antagonistic interactions and synergistic remediation traits (Rotoni et al., 2025; Geerdes et al., 2025). Field trials demonstrate that such consortia outperform single inoculants, with combined application of AM fungi and plant growth-promoting bacteria reducing heavy metal uptake while simultaneously increasing biomass production by 70-240% (Li et al., 2025). Critically, network analyses reveal that successful SynComs exhibit distinct community structures with abundant cross-kingdom interactions—bacteria providing B-vitamins and siderophores that fungi require, while fungi translocate carbon to bacterial partners.

Rational design of SynComs requires understanding the ecological principles governing microbial assembly in contaminated soils. Recent machine learning approaches applied to microbiome data have identified keystone taxa whose presence predicts community stability and function (Fernández-González et al., 2025). Bacterial genera including Actinophytocola, Nocardia, and Sphingomonas emerge as consistent network hubs in disease-suppressive soils, displaying negative interactions with pathogenic fungi. Incorporating such keystone bacteria into mycorrhizal inoculants could create self-stabilizing consortia resistant to pathogen invasion—a critical requirement for long-term field persistence.

Beyond genetic engineering of individual organisms, there exists potential for engineering mycorrhizal network topology itself. If hyphal networks function as distributed sensors and resource allocation systems, then manipulating network connectivity patterns could optimize remediation efficiency. For instance, establishing "contamination-sensing modules" where specific plant-fungus combinations respond to pollutants by altering exudate chemistry could trigger network-wide resource reallocation toward contaminated zones. While highly speculative, such approaches leverage the emergent properties of CMNs rather than simply optimizing individual components.

Decentralized Remediation: Design Principles and Implementation Challenges

Translating mycorrhizal remediation from laboratory curiosity to field-scale technology requires confronting fundamental design challenges. First, contaminated sites exhibit extreme spatial heterogeneity in pollutant distribution, soil chemistry, and microbial communities. A decentralized remediation system must be robust to such variability while remaining locally adaptive. Mycorrhizal networks inherently possess these properties—individual plants respond to local conditions while the network integrates information across scales. Field studies demonstrate that mycorrhizal community composition varies with soil pH, heavy metal concentration, and vegetation type, with networks self-organizing to match local conditions (Onoszko et al., 2025; Albornoz et al., 2025).

A critical implementation question concerns inoculum persistence and competitive exclusion. Contaminated soils often harbor dense communities of native fungi, and introduced inoculants must colonize plant roots despite competition from established symbionts (Coleman et al., 2025). Recent evidence suggests that early-stage inoculation—applying mycorrhizal fungi to seedlings in controlled nursery conditions—creates persistent metabolic shifts in rhizosphere bacterial communities that endure months after field transplantation, even when fungal community composition eventually converges (Moreno et al., 2025). This "metabolic memory" effect could be exploited to prime remediation systems, with nursery inoculation establishing functional states that persist despite taxonomic turnover.

Monitoring and adaptive management present additional challenges. Unlike engineered chemical processes with defined inputs and outputs, mycorrhizal remediation involves complex ecological dynamics requiring continuous assessment. Emerging metagenomic and metabolomic approaches enable real-time tracking of microbial community function and contaminant biotransformation pathways (Wen et al., 2025). Integration with remote sensing could create early warning systems where spectral signatures of plant stress indicate contamination hotspots requiring intervention. Such monitoring frameworks transform mycorrhizal networks into environmental sensor arrays, leveraging their spatial distribution for landscape-scale contamination mapping.

Economic and social dimensions fundamentally shape implementation feasibility. Phytoremediation using mycorrhizal partnerships offers cost advantages over conventional approaches—a field-scale study estimated costs at $50-200 per ton soil treated compared to $400-2000 for excavation and disposal (Neagoe et al., 2025). However, remediation timescales remain protracted, typically requiring 3-10 years for significant contaminant reduction. During this period, contaminated sites generate no economic value unless dual-use systems are implemented. Biofortification crops (accumulating nutrients in edible tissues) or biomass crops (producing renewable energy feedstocks) could generate revenue streams while remediating, though safety concerns about contaminant transfer to harvested products require rigorous assessment.

Future Horizons and Open Questions

Despite substantial progress, fundamental questions remain regarding mycorrhizal network function and remediation potential. First, the mechanisms by which mycorrhizal networks transfer information beyond simple resource exchange remain poorly understood. Do electrical signals propagating through hyphae carry meaningful information about environmental conditions? Could networks coordinate plant defense responses or optimize community-level carbon allocation? Addressing these questions requires integrating tools from network neuroscience—transfer entropy analyses, causal inference methods, and dynamical systems modeling—to mycorrhizal ecology (Fukasawa et al., 2024).

Second, the stability and predictability of engineered mycorrhizal systems in field conditions remains uncertain. Laboratory studies operate under controlled conditions eliminating the environmental variability, pathogen pressure, and species interactions characterizing natural ecosystems. Field trials frequently show reduced efficacy compared to greenhouse experiments, with SynCom performance varying dramatically across sites (Geerdes et al., 2025). Developing predictive frameworks that account for context-dependence—incorporating soil type, climate, native microbiome composition—is essential for translating research into practice.

Third, the potential for evolutionary adaptation in mycorrhizal remediation systems deserves investigation. Fungi evolving in contaminated environments show rapid adaptation to metal toxicity within decades (Lax et al., 2025). Could we accelerate such adaptation through directed evolution, selecting for fungi that thrive in contaminated soils while maximizing metal sequestration? Conversely, how do we prevent maladaptive evolution—for instance, fungi that colonize plants but fail to provide remediation services?

Finally, integration of mycorrhizal remediation with broader ecosystem restoration goals remains underexplored. Contaminated sites often suffer multiple degradation pressures—compaction, erosion, nutrient depletion, invasive species—requiring holistic restoration approaches. Mycorrhizal networks enhance soil aggregate stability, carbon sequestration, and plant community diversity, offering synergies beyond contaminant removal (Li et al., 2025). Optimizing these co-benefits while maintaining remediation efficacy represents a grand challenge for ecological engineering.

Conclusion

Mycorrhizal networks represent one of nature's most sophisticated biotechnologies—distributed sensing and resource allocation systems refined through hundreds of millions of years of evolution. By reconceptualizing these networks as environmental "neural networks" capable of adaptive, decentralized remediation, we open radical new possibilities for ecosystem restoration. The convergence of mycorrhizal ecology, synthetic biology, and network science enables us to not merely harness existing symbioses but to engineer enhanced capabilities—designer consortia optimized for specific contaminants, metabolically reprogrammed plants with augmented stress tolerance, and network topologies that maximize spatial coverage and resilience.

Yet realizing this vision requires humility about the complexity we seek to engineer. Ecosystems are not machines with predictable inputs and outputs; they are dynamical systems with emergent properties, feedback loops, and evolutionary potential. The most promising path forward lies not in replacing ecological complexity with engineered simplicity, but in working with—and learning from—the sophisticated systems evolution has already optimized. Mycorrhizal networks teach us that the most effective solutions may be distributed rather than centralized, adaptive rather than rigid, and emergent from local interactions rather than imposed from above.

As climate change intensifies and contaminated lands expand, the urgency of developing scalable, sustainable remediation technologies grows daily. Mycorrhizal-based systems offer a vision of restoration that is simultaneously ancient and futuristic—grounded in evolutionary partnerships while augmented by cutting-edge biotechnology. Whether this vision translates into transformative real-world impact depends on continued interdisciplinary collaboration, rigorous field validation, and willingness to reimagine what remediation can be. The mycorrhizal networks beneath our feet may hold keys not just to cleaning contaminated soils, but to fundamentally reshaping how we conceive of environmental technology in the 21st century.

References

- Albornoz, F. E. et al. (2025). Changes in soil microbial assemblages, soil chemistry, and vegetation composition associated with Eucalyptus viminalis dieback. Plant and Soil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-025-07407-5

- Coleman, M. D. et al. (2024). Status of truffle science and cultivation in North America. Plant and Soil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-024-06822-4

- Fernández-González, A. J. et al. (2025). Unveiling essential host genes and keystone microorganisms of the olive tree holobiont linked to Verticillium wilt tolerance. Microbiome, 13, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-025-02216-5

- Fukasawa, Y. et al. (2024). Electrical integrity and week-long oscillation in fungal mycelia. Scientific Reports, 14, 15215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66223-6

- Geerdes, N. et al. (2025). Synthetic microbial communities: Bridging research and application in second-generation bioenergy feedstock microbiomes. Plant and Soil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-025-07937-y

- Jiang, L. et al. (2025). Root mixing effects on belowground decomposition depend on mycorrhizal type. Nature Communications, 16, 1163. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65163-7

- Lax, C. et al. (2025). Unveiling a pervasive DNA adenine methylation regulatory network in the early-diverging fungus Rhizopus microsporus. Nature Communications, 16, 177. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65177-1

- Li, Z. et al. (2025). Synergistic superiority of AMF and biochar in enhancing rhizosphere microbiomes to support plant growth under Cd stress. Biochar, 7, 498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-025-00498-4

- Marrassini, V. et al. (2025). Positive response to inoculation with indigenous arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as modulated by barley genotype. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 45, 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-025-01016-3

- Moreno, B. et al. (2025). Early inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi shifts metabolic functions of rhizosphere bacteria in field-grown tomato plants. Plant and Soil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-025-07944-z

- Neagoe, A. et al. (2025). Increasing the fungal inoculation of mine tailings from 1 to 2% decreases plant oxidative stress and increases the soil respiration rate. Scientific Reports, 15, 14973. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14973-2

- Nuland, M. E. et al. (2025). Global hotspots of mycorrhizal fungal richness are poorly protected. Nature, 640, 277-284. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09277-4

- Onoszko, K. et al. (2025). Unravelling the diversity of soil fungal and oomycete communities in the Quercus ilex L. rhizosphere of dehesa grasslands: a metabarcoding approach. Plant and Soil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-025-08019-9

- Oubohssaine, M., Sbabou, L. & Aurag, J. (2025). Enhancing ecosystem restoration and soil productivity through PGPR: a sustainable approach to bioremediation and biofertilization. Discover Applied Sciences, 7, 510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-025-07510-3

- Parise, A. G. et al. (2025). How mycorrhizal fungi could extend plant cognitive processes. Symbiosis, 95, 65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13199-025-01065-y

- Pena, R. & Tibbett, M. (2024). Mycorrhizal symbiosis and the nitrogen nutrition of forest trees. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 108, 298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-024-13298-w

- Rotoni, C. et al. (2025). Synergy between AMF and accompanying microbiome enriched with PGPB enhances root development and microbiome dynamics. npj Sustainable Agriculture, 3, 81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00081-1

- Ryadin, A. R. et al. (2025). Fungal succession, litter decomposition and root nitrogen supply in a tropical oil palm plantation. Plant and Soil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-025-07962-x

- Severo, H. C. et al. (2025). Co-inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Bacillus subtilis enhances morphological traits, growth, and nutrient uptake in maize under limited phosphorus availability. Scientific Reports, 15, 10038. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10038-6

- Snyder, E., Simard, S. W. & Guichon, S. (2025). The arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities associated with Taxus brevifolia (western yew) are sensitive to soil pH and neighborhood forest composition. Scientific Reports, 15, 22917. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22917-z

- Soliman, S. et al. (2025). Strigolactone GR24 modulates citrus root architecture and rhizosphere microbiome under nitrogen and phosphorus deficiency. BMC Plant Biology, 25, 515. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-07515-5

- Tang, Z. et al. (2025). Synergistic application of canna-derived biochar and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhances cadmium immobilization and soil ecological function in contaminated soils. Scientific Reports, 15, 29752. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29752-2

- Usama, M. et al. (2025). Crosstalk between glomalin and AMF reduces cadmium uptake and leaching, enhancing pea yield and soil health. BMC Plant Biology, 25, 534. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-07534-2

- Wei, N., Nakaji-Conley, M. & Tan, J. (2025). Contrasting Diversity and Network Dynamics of Soil Fungal Functional Groups in the Plant Rhizosphere. Microbial Ecology, 90, 633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-025-02633-x

- Wen, S. et al. (2025). Effects of different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on tobacco seedling growth and their rhizosphere microecological mechanisms. BMC Plant Biology, 25, 600. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-07600-9

- Yang, X. et al. (2025). How do arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance drought resistance of Leymus chinensis? BMC Plant Biology, 25, 6412. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-06412-1